How U.S. history textbooks and prominent American universities justified slavery, perpetuated racial stereotypes and promoted white supremacy. |

John Gast's 1872 painting "American Progress," seen as an allegory for Manifest Destiny and American westward expansion. The painting serves as the cover for Donald Yacovone's “Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our N, |

You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear You’ve got to be taught from year to year It’s got to be drummed in your dear little ear You’ve got to be carefully taught You’ve got to be taught to be afraid Of people whose eyes are oddly made And people whose skin is a diff’rent shade You’ve got to be carefully taught You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late Before you are six or seven or eight To hate all the people your relatives hate You’ve got to be carefully taught With these haunting words from the 1949 Broadway musical “South Pacific” by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, Donald Yacovone opens his startling new book “Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity” (Pantheon). Equally revealing, and an important partner to Yacovone’s book, is Jessica Blatt’s “Race and the Making of American Political Science” (University of Pennsylvania). These impressive books describe how the institution of American education trained its teachers and taught its students to believe slavery was good for the enslaved, that Reconstruction was a disaster, that African Americans were innately inferior and that the destiny of the United States was to be ruled by the descendants of White Europeans. These books would have been welcome whenever they appeared, but they take on added urgency today as Republicans in Congress and several state legislatures across the country actively seek to turn back the clock by passing new laws to erase history and reimpose a white supremacist narrative in American education and by banning certain books and curriculums because they offer a thorough account of the ongoing struggle throughout American history to overcome racism, sexism, homophobia and bigotry. On January 12, the Florida Department of Education informed the College Board, which administers Advanced Placement exams, that Florida would not allow a new A. P. course on African American studies to be offered in its high schools, claiming the course is not “historically accurate,” “significantly lacks educational value” and violates state law. Last year, Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, signed legislation that restricted how racism and other aspects of history can be taught in schools and workplaces. The law’s sponsors called it the Stop WOKE Act. Among other things, the act prohibits instruction that could make students feel responsibility for or guilt about the past actions of other members of their race. The College Board said the course, a multiyear pilot program that has been used in 60 high schools across the country, including at least one in Florida, is multidisciplinary and addresses not just history but civil rights, politics, literature, the arts and geography. Florida law prohibits schools from teaching “critical race theory,” an academic framework for understanding racism in the United States, and does not allow educators to teach The 1619 Project, a classroom program developed by The New York Times that seeks to reframe the country’s history by putting the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the center of the national narrative. Henry Louis Gates Jr., a former chair of Harvard’s Department of African and African American Studies and director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, who was a consultant to the College Board as it developed the A.P. course, said last year that he hoped the curriculum would not shy away from such topics that spur debate, not as a framework, but as a way of studying different theories of the African American experience. It is imperative that we keep the focus on “systemic” racism in the United States. We must combat the notion that racism is simply a personal attitude that individuals happen to develop for which society as a whole bears no responsibility. In fact every U.S. institution — including our educational system — has been infected by, and has in turn perpetuated, deep-seated racial, ethnic, religious and gender biases, prejudices and stereotypes. Blatt’s illuminating study of the racist origins of political science in the United States sets the stage for Yacovone’s broader look at how textbooks in U.S. high schools and colleges intentionally advanced the ideology of white supremacy. These books complement and reinforce each other and contribute significantly to our understanding of how white supremacy has been tightly woven into the teaching of U.S. history. The Racist Origins of the Study of Political Science in America Based on copious research, Blatt, an associate professor of political science at Marymount Manhattan College, convincingly demonstrates that “race thinking shaped U.S. political science at its origins far more profoundly than has previously been recognized.” She explains that “the precept on which U.S. political science was founded in the late 19th century” was “the idea that our politics are born into us — indeed, specifically that some people are innately cut out for self-government and progress while others are by their constitutions more suited to traditional forms of authority.”

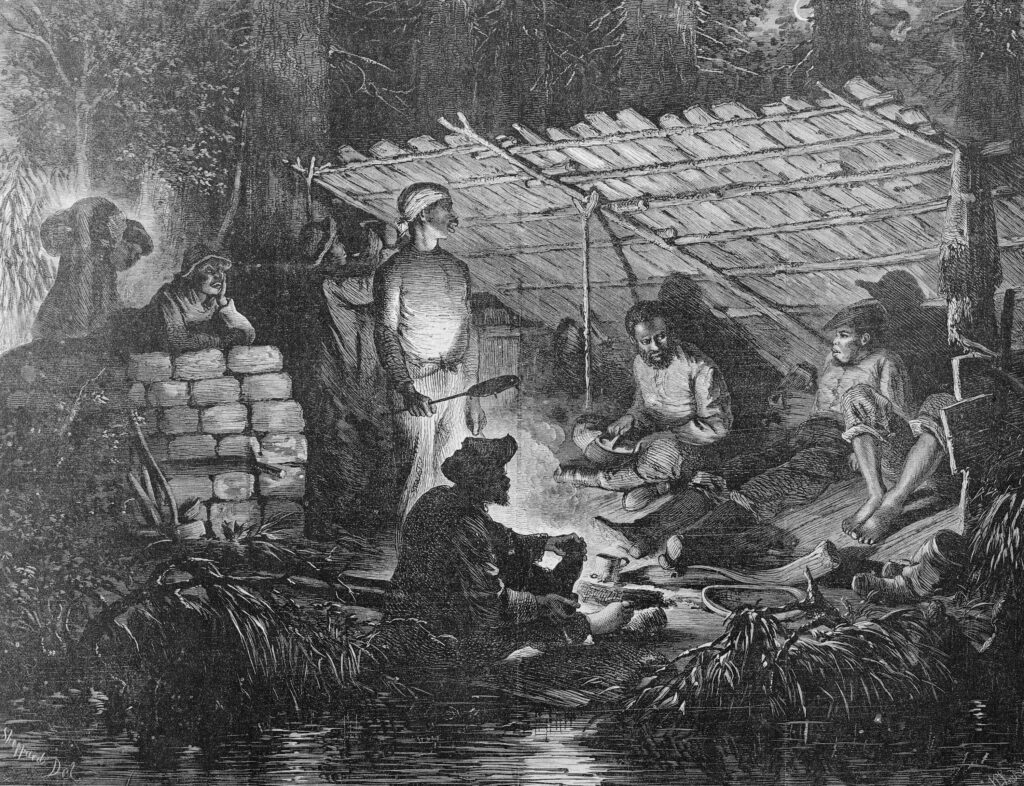

An illustration showing Black men and boys, former slaves, hiding in the swamps of Louisiana during the Reconstruction period in 1873. (AP Photo/NY Public Library), Well into the 20th century, “major political scientists understood racial difference to be a fundamental shaper of political life,” Blatt writes. “They wove popular and scientific ideas about racial difference into their accounts of political belonging, of progress and change, of proper hierarchy and democracy and its warrants.” She examines “how racial ideas figured in a number of settings in which pioneering U.S. political scientists sought to stake out their intellectual territory and define their methods.” These settings included Columbia University’s history department in the 1880s and 1890s; the meetings, publications and other activities of the American Political Science Association in the decade following its founding in 1903; the first U.S.-based international journal, the Journal of Race Development, founded in 1910; and the efforts in the 1920s by prominent academics to bring their version of scientific methods to bear on political questions and “to integrate the study of politics into an interdisciplinary social science matrix” at major universities across the country. Blatt introduces us to one of the founders of political science in the United States, John W. Burgess, who established one of the first doctoral programs in politics in the nation. A constitutional scholar, teacher of future presidents and prominent commentator on domestic and foreign affairs, he was born in 1844 to a slave-holding Union family in Tennessee and spent his adult life among the Northern elite. He fought for the Union Army in the Civil War and studied history at Amherst College and at several German universities. In 1876, he was appointed to a professorship at the law school at what would later become Columbia University, where he continued to teach until his retirement in 1912. In 1886, he founded the Political Science Quarterly. In an early volume of PSQ, a prominent scholar wrote that the “negro [was] not an Anglo-Saxon, or a Celt or Scandinavian — only underdeveloped and with black skin….The African [was] on the contrary a wholly distinct race, and the obstacles to social equality and political co-efficiency” with “our own” race were “not factious but anthropological.” From the late 19th century into the 20th, Black people appeared in the pages of PSQ and in papers published in the American Political Science Review as the “half-civilized,” “alien” element within the American population; as “permanent[ly]…indolent and thriftless,” “unfit to vote,” lacking “initiative and inventive genius and prone to chicken-stealing,” “savage,” and determined to “outrage and murder” Southern whites’ “young daughters.” Burgess was “an especially committed and vehement racist,” Blatt writes, “even by the standards of late 19th century America.” Together with his one-time student William A. Dunning (who would soon play his own prominent role in spreading this racial ideology), he cemented the image of Reconstruction as a “hideous tyranny” of “negro domination.” He wrote that “black skin means membership in a race of men which has never of itself succeeded in subjecting passion to reason, has never, therefore, created any civilization of any kind.” Burgess described the Black-led Reconstruction legislatures of South Carolina and Louisiana as “the most soul-sickening spectacle that Americans had ever been called to behold” and the legislators themselves as “ignorant barbarians.” According to Blatt, Burgess “held firmly that ‘American Indians, Africans and Asiatics’ ought never to ‘form any active, directive part of the political population’ in the United States and was skeptical about the wisdom of extending the suffrage to many non-Aryan whites.” At one of the most esteemed American universities, Burgess taught that “Anglo-Saxons were the bearers of a ‘Teutonic germ’ of liberty” which “carried forward the potential of civilization,” Blatt writes. “As for the rest, some might eventually be assimilated, but most were more suited to authoritarianism (at home) and colonial domination (abroad).” Consequently, the “first U.S.-trained cohort of political science Ph.D.s learned that adhering to a priori fictions of equality and social contracts had only resulted in the disaster of the Civil War.” Blatt explains that as political science began to take shape within the academy “leading practitioners put racialist premises at the heart of their account of democratic legitimacy and sovereignty, the dynamics of political change and the propriety and limits of political reform.” Even slavery, to which Burgess described himself as “strongly hostile,” was justifiable in its time “as a relation which could temporarily produce a better state of morals in a particularly constituted society than any other relation.” It was the “white man’s mission,” indeed “his duty and his right,” to “hold the reins of political power in his own hands for the civilization of the world and the welfare of mankind.” In the classroom and in his extensive scholarly writings, Burgess taught that any participation in government of “non-Teutonic” people was a recipe for “corruption and confusion,” since only “the Teuton” possessed a “superior political genius.” Inspired by Burgess, Dunning, who was born in Plainfield, New Jersey and educated at Dartmouth College, would get his doctorate at Columbia where he would remain his entire career, rapidly rising to the Leiber professorship of history and political philosophy. He taught generations of scholars, who in turn taught generations of students, in what became known as the Dunning School of Reconstruction, a historiographical school of thought, which, according to leading historian Eric Foner, “was part of the edifice of the Jim Crow system.” It claimed that “Black people are incapable of taking part in American democracy,” thereby justifying denying them the right to vote on the grounds they abused it during Reconstruction. It may come as a surprise to many that the most famous acolyte of the racist ideology promoted by Burgess, Dunning, and their growing cadre, was the 28th president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson. After earning a Ph.D. in political science from Johns Hopkins University, Wilson taught at various universities before becoming the president of Princeton University. While he criticized the Burgess-style of political science as too legalistic and unmoored from any empirical foundation, Wilson maintained many of Burgess’s racist precepts, including, as Blatt puts it, “a racialized conception of the collective shaping and authorizing government.” According to Blatt, Wilson’s well-received 1889 textbook, “The State,” rehearsed the familiar themes of “the Aryan origins of the Anglo-American political tradition; a link between Teutonic history and the development of individual liberty; [and] an explicit rejection of universalizing, natural law or social-compact theory.” Blatt then traces the direct line from these racist theories to the widespread promotion of eugenics, especially within the Progressive movement, which saw it as a benevolent way to “improve society.” A leading proponent of eugenics, Charles B. Davenport, established the Galton Society in 1918 and housed it within the American Museum of Natural History. Davenport was the founder of the prestigious Department of Experimental Biology and the Eugenics Record Office, both at Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island. One historian of this period calls Davenport “the most prominent racist among American scientists” at the time. He would spend his career promoting forced sterilization and institutionalizing the “unfit.” In sum, Blatt writes, “[a]cross generational and theoretical divides, political scientists were united in a near-consensus that African Americans were inferior, politically incompetent and unsuited to live under a legal system constituted by and for Anglo-Saxons.” Consequently, “by their very presence in the United States African Americans challenged social peace and the viability of constitutional principles, and any attempt to integrate them into American democracy necessarily stemmed from a catastrophic misunderstanding of that basic truth.” Beyond Burgess, Dunning, Wilson and Davenport, Blatt describes scores of other prominent professors at prestigious colleges and universities around the country who taught these gravely flawed ideas and gave legitimacy to these racist ideologies. The real world consequences were devastating. According to Blatt, what developed “was a consensus that the emerging Jim Crow regime of racial segregation and stratification represented a moderate, pragmatic response to the realities of racial difference.”

Lithograph of Horatio Bateman’s allegorical illustration of the reconciliation between the North and the South following the end of the Civil War and the beginning of the Reconstruction Era. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Blatt has written an important book that reveals in detail how American institutions, such as the study of political science, are not neutral bystanders in our nation’s reluctant reckoning with its racist past. Instead, “Race and the Making of American Political Science” concretely establishes, based on the firsthand evidence of what the founders of this academic discipline themselves wrote and taught, that political science as developed in the United States was drenched in the rhetoric of white supremacy. It energetically embraced this racist ideology and offered it to students and the public at large as the most historically and scientifically authentic narrative of America’s founding and destiny. The most respected scholars of their day, teaching at the most prestigious institutions of higher learning, anointed white supremacy with a priceless seal of approval. It would take courageous dissenting voices over several decades, including the proponents of critical race theory, reinforcing the civil rights movement, to challenge the prevailing paradigm of white supremacy. Current efforts to demonize critical race theory and marginalize efforts to address systemic racism are alarming proof that we have a long way to go to dismantle white supremacy. Blatt’s revealing book is an indispensable tool in that long overdue project. How U.S. Textbooks Taught White Supremacy to Generations of American Students In “Teaching White Supremacy,” Donald Yacovone widens the lens to explain the broader historical and cultural context that preceded and overlaps the developments so ably explored by Jessica Blatt in “Race and the Making of American Political Science.” Yacovone is a lifetime associate at Harvard’s Center for American & African American Research, the winner (with Henry Louis Gates) of a 2014 NAACP Image Award for “The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross,” and a recipient of the W.E.B. Du Bois Medal from Harvard University in 2013. To examine the “depth, breadth, and durability of American white supremacy and racial prejudice,” Yacovone chooses the very ordinary and ubiquitous institution that every impressionable student has trusted and relied on to learn history: textbooks. So familiar and so easily overlooked, textbooks have been a persistent instrument of white supremacy hiding in plain sight. “Embodying the values to be treasured by rising generations of Americans, textbook authors passed on ideas of white American whiteness from generation to generation,” Vacovone writes. “Writers crafted whiteness as a national inheritance, a way to preserve the social construction of American life and ironically, its democratic institutions and values.” He frames his book as “an exploration of the origins and development of the idea of white supremacy, how it has shaped our understanding of democratic society and how generation after generation of Americans have learned to incorporate that vision into their very identity.” Vacovone quotes celebrated African American writer and critic James Baldwin, who in 1965 wrote, “I was taught in American history books that Africa had no history and that neither had I. I was a savage about whom the least said the better, who had to be saved by Europe and who had to be brought to America.” Vacovone readily acknowledges that he is not the first to identify the role textbooks have played in propagating white supremacy in America. In 1939, the NAACP surveyed popular American history textbooks. Vacavone quotes a Black student who concluded that since textbooks “drilled” white supremacy “into the minds of growing children, I see how hate and disgust is motivated against the American Negro.” But his book is today the most comprehensive examination of this subject, rich in detail, allowing us “to trace exactly how white supremacy and Black inferiority” were taught as the prevailing historical account of American history. A major goal of Yacovone’s book is to debunk the notion of blaming the persistence of racial inequality only on the legacy of Southern slavery. While “slave owners and their descendants do possess a unique and lethal responsibility for racial suppression,” he writes, “if no slaves ever existed in the South, Northern white theorists, religious leaders, intellectuals, writers, educators, politicians and lawyers would have invented a lesser race (which is what happened) to build white democratic solidarity, and in that way make democratic culture and political institutions possible.” Ending slavery did not end racism. Rather than Southern slavery, Yacovone writes, “it was Northern white supremacy that proved the more enduring cultural binding force, planted along with slavery in the colonial era, intensely cultivated in the years before the Civil War, and fully blossoming after Reconstruction. Inculcated relentlessly throughout the culture and in school textbooks, it suffused Northern religion, high culture, literature, education, politics, music, law and science.” As Yacovone sees it, “history textbooks proved a perfect vehicle for the transmission” of the idea of white supremacy. U.S. history textbooks began to significantly increase in the 1820s as New England, New York and parts of Virginia established publicly supported high schools that mandated the teaching of history. The demand for textbooks blossomed in the 1890s when several American publishers formed the American Book Company. By 1912, annual textbook sales soared to at least $12 million (about $300 million in modern currency). Six years later sales had almost doubled. By 1960, fifty U.S. textbook publishers earned about $230 million annually, which leaped to over half a billion by 1967. Far from “mere aggregations of dead facts,” Yacovone writes, “history texts served as reservoirs of values, patriotism and national ethos,” which sought “to create unity through storytelling, creating a national identity that could serve as a road map to the future.” While he agrees that history textbooks are the “prayer books” of our national civil religion, Yacovone is quick to point out that “we have been selective in what we cherish in them and blind to what, in time, has proven disconcerting, if not shameful and humiliating.” He traces this dreadful history in vivid detail, filled with scores of cringe-worthy examples of appallingly racist material passed on to students as historical fact. Much of it can be traced to John H. Van Evrie, whom Yacovone calls “the nation’s first professional racist,” who “worked tirelessly to permanently bind white supremacy to the nation’s democratic ethos.” Born in Canada and raised in Rochester, New York, Van Evrie partnered with Rushmore G. Horton to form a small publishing empire, Van Evrie, Horton & Co, in the heart of Manhattan. They published, among many titles, Horton’s history textbook,” A Youth’s History of the Great Civil War in the United States.” The book was designed, according to Yacovone, “to repudiate the policies of the Lincoln administration, reject all political or social equality for African Americans and guarantee that future generations would cherish white supremacy as the nation’s governing principle.” In particular, the book attacked the program of Reconstruction. In the wake of the Civil War, Congress enacted Reconstruction to incorporate freed people and Northern Blacks into American society with equal constitutional protections and responsibilities. As Eric Foner, the country’s leading authority on Reconstruction, has written, in the South it was “a massive experiment in interracial democracy without precedent in the history of this or any other country that abolished slavery in the 19th century.” During Reconstruction, 16 African Americans would serve in Congress, more than 600 in state legislatures, and hundreds more in local offices from sheriff to justice of the peace across the South. The era represented, in Yacovone’s words, “a colossal effort to transform and refound the nation and its governing principles: in short, to eliminate the world as Van Evrie understood it.” Slavery may have been abolished, but because Reconstruction threatened to dismantle white supremacy, it had to be dismantled — not only in fact but in historical memory. President Andrew Johnson did all he could to undermine it, and white Southerners resisted it at every turn, led by the emerging Ku Klux Klan. In the end Reconstruction lasted only 12 years and was replaced by a resurgence in white political control, Jim Crow laws, disenfranchisement of Black voters and full-blown segregation. And to justify this sorry result, history textbooks were pressed into service to demonize Reconstruction generally, glorify the KKK, in particular, and promote the Lost Cause mythology to recast the entire history of the South and frame the Civil War as a constitutional assertion of “states rights.” Yacovone is particularly adept in developing this shameful period. Reconstruction was labeled a “failure” because Blacks were innately inferior (“ignorant and timid,” “poverty-stricken ignoramuses,” “with a ballot in his hands he is a menace to civilization”) and therefore unable to govern. Meanwhile, textbooks taught that the KKK, made up of many former Confederate soldiers who were “seeking merely fun and excitement,” represented a noble effort to protect the “homes and women of the South” from “pillage, and other outrages of the negroes.”

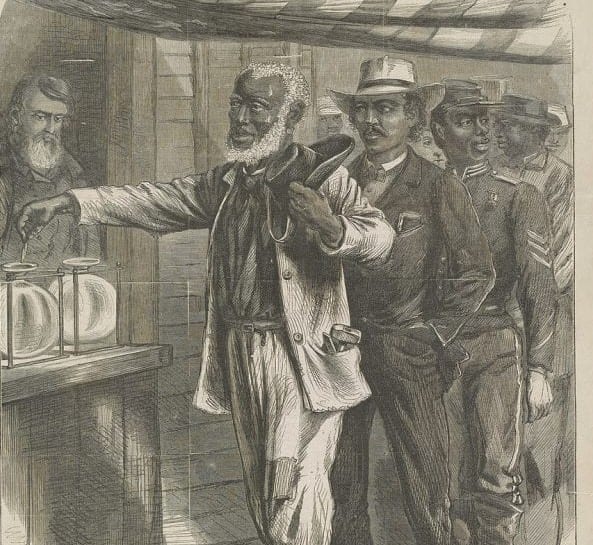

“The first vote” (Drawn by A.R. Waud/Library of Congress). At the same time, in textbook after textbook, the North never flagged in promoting white supremacy. For example, in 1896, Samuel Train Dutton was superintendent of schools in Brookline, Massachusetts, when he wrote the ever-popular “Morse Speller,” which enjoyed its 13th edition in 1903. In it he wrote: “To the Caucasian race by reason of physical and mental superiority, has been assigned the task of civilizing and enlightening the world.” Vacovone reports that at the advent of the 20th century, “the overwhelming majority of American textbooks” began with the assumption underlying Thomas Maitland Marshall’s popular “American History,” first published in 1930, that “the history of the United States was the history of the white man, his struggles against Native Americans (usually rendered as ‘red savages’), and his need to control the lives of African Americans,” who sought to destroy “the superior race.” Marshall, a professor of history at Washington University in St. Louis, began his textbook with the headline “THE STORY OF THE WHITE MAN.” Typical among these prominent textbooks, Marshall said very little about the establishment and growth of slavery, preferring instead to dwell on “slave character.” Regardless of his situation or condition, the negro of plantation days was usually happy. He was fond of the company of others and liked to sing, dance, crack jokes and laugh; he admired bright colors and was proud to wear a red or orange bandana….He was never in a hurry, and was always ready to let things go until the morrow. Most of the planters learned not to whip, but loyalty, based on pride, kindness and rewards, brought the best returns. Leading textbooks written by prominent historians like James Ford Rhodes, president of the American Historical Association, relied on “science” promoted by scholars such as Harvard University’s famed ethnologist Louis Agassiz, and informed their readers that Blacks were either a separate species or vastly inferior humans, “indolent, playful, sensual, imitative, subservient, good, natured, versatile, unsteady in purpose, devoted and affectionate.” With shocking example after example, Yacovone establishes, simply by quoting the textbooks themselves, that until the mid-1960’s, “American history instruction from grammar school to the university relentlessly characterized slavery as a benevolent institution, an enjoyable time and a gift to those Africans who had been lucky enough to be brought to the United States.” “The history we teach,” Yacovone observes, “is the product of the culture we create, not necessarily of the actual history we made.” He cites Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Leon Litwack who blamed historians as the one group of scholars most responsible for the “mis-education of American youth” and for doing the most to warp “the thinking of generations of Americans” on the issue of race and African Americans. In “The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society” (1998), Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. bluntly declared that “white Americans began as a people so arrogant in convictions of racial superiority that they felt licensed to kill red people, to enslave black people, and to import yellow and brown people for peon labor. We white Americans have been racist in our customs, in our conditioned reflexes, in our souls.” And, as Blatt and Yacovone have so ably demonstrated, in our textbooks and political science. How the Legacy of Teaching White Supremacy Lives On The lasting value of the excellent books by Blatt and Yacovone is to equip us to confront the renewed, widespread and coordinated efforts by conservative lawmakers to erase the grudging progress that has been made since the 1960s in teaching American history and replace it with a modern version of the racist textbooks and distorted political science these authors have exposed. In April 2022, PEN America, the literary and free expression advocacy organization, released an alarming study entitled “Banned in the USA: Rising School Book Bans Threaten Free Expression and Students’ First Amendment Rights.” It documents decisions to ban books in school libraries and classrooms in the United States from July 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022. The study concluded that “state legislators are introducing — and in some cases passing — educational gag orders to censor teachers, proposals to track and monitor teachers, and mechanisms to facilitate book banning in school districts.” PEN America noted “a profound increase in both the number of books banned and the intense focus on books that relate to communities of color and LGBTQ+ subjects.” In total, for the nine-month period in question, PEN America listed 1,586 instances of individual books being banned, affecting 1,145 unique book titles by 874 different authors, 198 illustrators and 9 translators, impacting the literary, scholarly and creative work of 1,081 people in 86 school districts in 26 states, representing 2,899 schools with a combined enrollment of over 2 million students. Of all bans listed, 41% (644 individual bans) are tied to directives from state officials or elected lawmakers to investigate or remove books in schools. The report calls this “an unprecedented shift in PEN America’s long history of responding to book bans, from the more typical pattern in which demands for book removals are initiated by local community members.” Among the banned titles, PEN America found “common themes reflecting the recent backlash and ongoing debates surrounding the teaching and discussion of race and racism in American history, LGBTQ+ identities and sexual education in schools”: 467 contain protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color (41%), and 247 directly address issues of race and racism (22%); 379 titles (33%) explicitly address LGBTQ+ themes, or have protagonists or prominent secondary characters who are LGBTQ+; 283 titles contain sexual content of varying kinds (25%), including novels with sexual encounters as well as informational books about puberty, sex, or relationships. There are 184 titles (16%) that are history books or biographies. Another 107 titles have themes related to rights and activism (9%). The PEN America report confirms that “these bans are overwhelmingly happening in districts where school authorities are not following best practice guidelines to protect students’ First Amendment rights, often making opaque or ad hoc decisions, in some cases in direct contravention of existing policies.” These findings overlap and align with those recently released by the American Library Association (ALA) in 2021, which document “an unprecedented number of book bans in public schools and libraries.” According to the ALA report, in 2021, “libraries found themselves at the center of a culture war as conservative groups led a historic effort to ban and challenge materials that address racism, gender, politics and sexual identity. These groups sought to pull books from school and public library shelves that share the stories of people who are gay, trans, Black, Indigenous, people of color, immigrants and refugees.” The ALA was quick to note that “we know that banning books won’t make these realities and lived experiences disappear, nor will it erase our nation’s struggles to realize true equity, diversity and inclusion.” For example, the ALA reports that Texas State Rep. Matt Krause sponsored a bill prohibiting schools from teaching lessons that might make students feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress” because of their race. Krause also wrote to a number of Texas school districts, demanding to know if the districts’ libraries included any of the 849 books listed in his letter. The list, comprising primarily books that address the experiences of Black and LGBTQIA+ people, spurred a number of school and public libraries to remove books from library shelves. According to the ALA report, “librarian Angie Manfredi put the situation in perspective when she said that some of the book ban backers don’t want children to learn about the experiences of underrepresented groups, including African Americans and LGBTQIA+ people.” In January 2022, PEN America also issued a comprehensive report entitled “Educational Gag Orders,” which disclosed that state legislatures across the United States were considering legislation “intended to restrict teaching and training in K-12 schools, higher education and state agencies and institutions.” The majority of these bills “target discussions of race, racism, gender and American history, banning a series of ‘prohibited’ or ‘divisive’ concepts for teachers and trainers operating in K-12 schools, public universities and workplace settings.” The report finds that the “bills appear designed to chill academic and educational discussions and impose government dictates on teaching and learning.” The report identified that between January and September 2021, 54 separate bills were introduced in 24 legislatures. Since then, PEN America has continued to track these kinds of bills. As of January 2023, the total number of bills jumped to a whooping 227 in 40 states. All of the bills have been introduced by Republicans. The report concluded that Collectively, these bills are illiberal in their attempt to legislate that certain ideas and concepts be out of bounds, even, in many cases, in college classrooms among adults. Their adoption demonstrates a disregard for academic freedom, liberal education and the values of free speech and open inquiry that are enshrined in the First Amendment and that anchor a democratic society. Legislators who support these bills appear determined to use state power to exert ideological control over public educational institutions. Further, in seeking to silence race- or gender-based critiques of U.S. society and history that those behind them deem to be “divisive,” these bills are likely to disproportionately affect the free speech rights of students, educators and trainers who are women, people of color and LGBTQ+. In addition, the “bills’ vague and sweeping language means that they will be applied broadly and arbitrarily, threatening to effectively ban a wide swath of literature, curriculum, historical materials and other media, and casting a chilling effect over how educators and educational institutions discharge their primary obligations.” According to PEN America, “the movement behind these bills has brought a single-minded focus to bear on suppressing content and narratives by and about people of color specifically—something which cannot be separated from the role that race and racism still plays in our society and politics. As such, these bills not only pose a risk to the U.S. education system but also threaten to silence vital societal discourse on racism and sexism.” PEN America noted that it is “not a coincidence that this legislative onslaught followed the mass protests that swept the United States in 2020 in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. As many Americans and U.S. institutions have attempted a true reckoning with the role that race and racism play in American history and society, those opposed to these cultural changes surrounding race, gender and diversity have pushed back ferociously, feeding into a culture war.” In particular, the report found that certain “Republican legislators and conservative activists have capitalized on this backlash, borrowing the name of an academic framework — critical race theory (CRT) — and inaccurately applying it to a range of ideas, practices and materials related to advancing diversity, equity or inclusion.” This “critical race theory” framing device has been applied with a broad brush, with targets as varied as The New York Times’ 1619 Project, the efforts to address bullying and cultural awareness in schools, and even the mere use of words like “equity, diversity and inclusion,” “identity,” “multiculturalism” and “prejudice.” Echoing what Blatt and Yacovone found, “Educational Gag Orders” reveals that these “bills will have—and are already having—tangible consequences for both American education and democracy, both distorting the lens through which the next generation will study American history and society and undermining the hallmarks of liberal education that have set the U.S. system apart from those of authoritarian countries.” PEN America points out that the “teaching of history, civics and American identity has never been neutral or uncontested, and reasonable people can disagree over how and when educators should teach children about racism, sexism and other facets of American history and society.” But it warns that “in a democracy, the response to these disagreements can never be to ban discussion of ideas or facts simply because they are contested or cause discomfort. As American society reckons with the persistence of racial discrimination and inequity, and the complexities of historical memory, attempts to use the power of the state to constrain discussion of these issues must be rejected.” Therefore, PEN America intends “to sound the alarm and recognize these bills for what they are: attempts to legislate constraints on certain depictions or discussions of United States history and society in educational settings; to stigmatize and suppress specific intellectual frameworks, academic arguments and opinions; and to impose a particular political diktat on numerous forms of public education.” “Teaching White Supremacy” and “Race and the Making of American Political Science,” as well as PEN America, the American Library Association and a growing number of other organizations and individuals are sounding the very same alarm. Will we return to a time when American institutions were free to teach racism and white supremacy as the accepted account of this nation’s history and destiny? Or will Americans — students of all ages — be carefully taught that the universal dignity and worth of every person entitles them to equality, inclusion and justice free of hatred, bigotry and discrimination? Stephen Rohde is a constitutional scholar, lecturer, writer, political activist and retired civil rights lawyer. He is the author of “American Words of Freedom” and “Freedom of Assembly,” and is a regular contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books and Los Angeles Lawyer magazine.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment